The Oxford Movement

"Blest are the pure in heart, for they shall see our God. The secret of the Lord is theirs; Their soul is Christ's abode." from Keble's lyrics for the hymn "Franconia", or #656 in the Episcopal hymnal

I think all of us can acknowledge that sermons in the 21st century are relatively innocuous. We might appreciate a good point made, nod at an affirmation of our worldview, smile at a clever turn of phrase or a witty remark.

They no longer have the power radically to change our culture, it seems.

Those of us who grew up during the 1960s and would hear Martin Luther King Jr. on the evening news certainly have memories of powerful moments of Christian proclamation. But those are days gone by. Christianity is no longer as influential in our culture.

Imagine a sermon, just a sermon, given in the midst of a collection of lawyers and judges at the beginning of the formal opening of the court, that managed to spin the entire history of English-speaking Christianity.

It began what history calls The Oxford Movement.

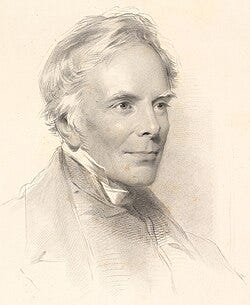

In July of 1833, John Keble, an Anglican priest and highly respected professor of poetry at Oxford University, took to the pulpit at the University Church of St. Mary the Virgin on High Street. It was expected to be a thoughtful and lyrical sermon, as befitting a man of letters addressing a rather staid body of professionals.

After all, Keble was many things, but mostly known for his quiet manner. He had just written a series of meditative poems for each of the Sundays and feast days of the year and his congregation was interested in hearing portions of that volume.

Instead, to paraphrase a beloved mentor of mine, he took to the pulpit and “breathed God’s own righteous fire” upon the parish, the profession, the greater church, and England.

“If we once make up our minds that the Church of Christ is a mere creature of the State, we shall soon learn to treat it accordingly.”1

As a true Anglican, he did so calmly and quietly, allowing his words to carry the power.

Once you make up your mind never to stand waiting and hesitating when your conscience tells you what you ought to do, and you have got the key to every blessing that a sinner can reasonably hope for.2

[I sometimes wish that I had temporary possession of a workable time machine so I could see the reaction from the pews. It must have been a wonderful sight.]

The sermon’s title was “A National Apostasy”, in which Keble criticized, in language both poetic and pungent, the manner in which the crown and parliament were insinuating themselves into church affairs.

[Historically, the crown in particular can have a rather heavy footprint in its religious dealings.]

Keble lit the fuse for something that had been fermenting ever since the “Dissolution of the Monasteries” by Henry VIII between 1536 and 1541, when the monastic houses in England, Wales, and Ireland were royally disbanded, their wealth seized by the king3, and their properties destroyed. This lead to a wide-spread reformation of all of the British parishes.

To highlight Henry’s resolve in this matter, there was one abbot who attempted to plead his monastic order’s case directly with the king at Buckingham Palace. The monarch’s response was for the abbot to be drawn and quartered, with his dismembered limbs suspended from the lychgate of his abbey. I believe his head was kept as a royal conversation piece.

With their dissolution, and the departure of the “English church” from the Church of Rome, the new Church of England rid itself of all “Romish” features, altered liturgical practices by removing devotional statuary, and diminished the focus on the Holy Communion, or Mass, from common worship.

This left a church that was more Puritan than it was Catholic. It would become a growing fixture of contention, especially after Oxford scholars two centuries later would begin to explore not just the devotional quality that had been lost, but the theological richness of sacramental Anglicanism.

So, they began to call for a restoration of these lost portions.

Being academics, and used to doing things in a logical, formal, and polite manner, the Oxford dons published a series of pamphlets, or tracts, that illuminated their position.

Being a bureaucracy dedicated to being as empty a spiritual shell as possible4, the Church of England responded first by wildly ignoring the tracts, then by chastising the Tractarians, as they had come to be known.

The tracts, known under the collective title of Tracts for Our Times, varied in length from short leaflets to longer, book-length works, and were produced by Keble and others. The series began with short pieces in 1833, the year of Keble’s sermon, then later of a more substantial length as they began to address more weighty doctrinal topics.

So the tension existed when Keble, the most unlikely of boat-rocking revolutionaries, decided to push at the envelop of propriety.

Keble called for a renewed focus on the Holy Eucharist and an expansion of liturgical practices to include devotionals, voluntary confession, and the restoration of monastic life.

He urged The Church of England to withstand the power dynamics being exercised upon them by the government and claim separation from their authority.

I have a feeling that this made for rather excitable conversations by those later gathered around the vicar’s sherry cabinet.

As fire is kindled by fire, so is a poet’s mind kindled by contact with a brother poet.5

Keble was not alone as he was backed by a formidable collection of The Church of England’s most accomplished and respected intellects and divines, almost all of whom were associated with Oxford University.

To say it caused a ruckus is an understatement.

The deeds we do, the words we say,—

Into still air they seem to fleet,

We count them ever past;

But they shall last,

In the dread judgment they

And we shall meet!6

Before it was over, the Oxford Movement would re-establish devotional aspects to worship and renew a focus on the power and efficacy of the Mass and its elements. This would not be a simple change in prayer book language and rubrics, though. There was a great amount of sturm and drang, with some of the Tractarians leaving the Church of England for the Church of Rome and others banned from preaching, teaching, or holding pastoral office.

[We will speak of the aftermath of Keble’s sermon next week.]

As for John Keble, despite being the comet that lights and ignites The Oxford Movement, he would be relatively unscathed in its wake. In fact, he would, upon his retirement from his professorship at Oxford, serve the remainder of his days as vicar of a parish in Hampshire.

We should note that he was a highly respected figure, probably politically untouchable by petty punishment. Just four years after his death, Oxford University would name its newest college for him.

So, if the reader has ever enjoyed chanting the psalm or sursum corda while in church, or appreciated the subtle symbolism of wafting incense, or prayed at a votive station before a patron’s statue, or crossed oneself on receiving a blessing, or partake of the Holy Communion on a weekly basis, we can thank John Keble, his words, his poetry, and, in particular, his courageous preaching, for helping to restore those lost items to our worship.

His happy magic made the Anglican Church seem what Catholicism was and is.7

Keble’s feast day is March 29.

Grant, O God, that in all time of our testing we may know your presence and obey your will, that, following the example of your servant John Keble, we may accomplish with integrity and courage what you give us to do and endure what you give us to bear; through Jesus Christ our Lord, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. Amen.

from Keble’s sermon, “A National Apostasy”.

from Keble’s Sermons for the Christian Year [1827].

The real reason for Henry’s sudden ecclesial interest.

Nothing new, in other words.

from Keble’s Lectures on Poetry 1832–1841

from Keble’s Lyra Innocentium [1846]

from the correspondence of John Henry Newman in reflection on his friend, Keble [1846?]

This is facinating history - I never knew a single sermon could have such lasting impact on an entire branch of Christianity. The idea that someone could 'breathe God's own righteous fire' in such a calm, measured way is kind of remarkable. It's intresting how these liturgical practices we take for granted today were actually revolutionary recoveries. I remember visiting Keble College a few years back and wondering about the name, now it all makes sense.